The concept of reversing aging has long been a tantalizing prospect in the field of biomedical research. Recent breakthroughs in epigenetic clock manipulation have brought this idea closer to reality, raising both excitement and caution among scientists. At the heart of this discussion lies a critical question: how much epigenetic resetting is safe before we trigger unintended consequences? Researchers are now grappling with establishing safety thresholds for epigenetic interventions that could potentially turn back the biological clock without causing cellular chaos.

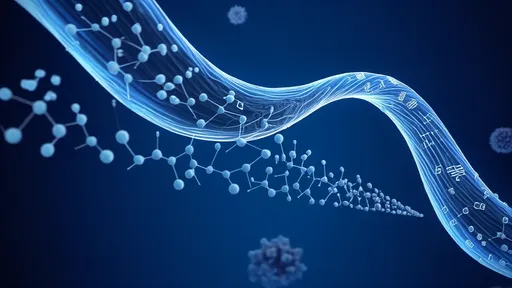

Epigenetic clocks, which measure biological age based on DNA methylation patterns, have emerged as powerful tools for understanding the aging process. These molecular timekeepers can detect accelerated aging in individuals exposed to stress, poor lifestyle choices, or environmental toxins. More remarkably, they've shown that certain interventions can slow down or even reverse these methylation patterns. However, the scientific community remains divided on how far we should push this reversal before crossing into dangerous territory where cells might lose their identity or become prone to malignant transformation.

The most promising research comes from partial reprogramming experiments using Yamanaka factors. When applied briefly to aged cells, these reprogramming factors can erase some epigenetic marks of aging without fully resetting cells to an embryonic state. This delicate balance between rejuvenation and maintaining cellular identity represents the frontier of current anti-aging research. Animal studies have demonstrated that controlled epigenetic resetting can extend lifespan and improve organ function, but the same techniques pushed too far result in teratomas or loss of tissue specificity.

Human trials exploring epigenetic age reversal remain limited, but early data suggests the potential exists within certain boundaries. Researchers analyzing blood samples from participants in various longevity interventions have observed modest but statistically significant decreases in epigenetic age. These changes typically range from 1-5 years of biological age reduction, leading some experts to propose this as a potential initial safety window. However, the long-term effects of even these small reversals remain unknown, particularly regarding how they might affect stem cell populations or cancer risk over decades.

One particularly thorny issue involves tissue-specific responses to epigenetic resetting. Different organs appear to have varying resistance to reprogramming, with some showing remarkable regenerative capacity and others potentially vulnerable to dysfunction. The brain, for instance, might benefit from selective epigenetic remodeling in glial cells but could suffer catastrophic consequences if neurons lose their specialized epigenetic patterning. This variability complicates the establishment of universal safety thresholds and suggests that future therapies may need to be highly tissue-specific.

The immune system presents another complex challenge in epigenetic age reversal. Certain immune cells rely on precise methylation patterns for their function, and disturbing these could either enhance immune surveillance or trigger autoimmune reactions. Recent studies of centenarians reveal that their immune systems maintain youthful epigenetic profiles longer than other tissues, hinting that controlled epigenetic maintenance rather than radical resetting might be the wiser approach for this critical system.

Beyond cellular concerns, researchers must consider the broader organismal effects of epigenetic interventions. Early evidence suggests that resetting the epigenetic clock in one tissue might create imbalances with other biological systems that haven't undergone similar rejuvenation. This mismatch could theoretically lead to new types of age-related pathologies even as certain markers of aging improve. The concept of "youthful enough" rather than "as young as possible" is gaining traction as a guiding principle for safe interventions.

Ethical considerations also weigh heavily on this emerging field. If safe thresholds for age reversal are established, questions about equitable access and societal impacts will become unavoidable. The medicalization of aging could create new categories of health disparity, while extended healthspans might strain pension systems and intergenerational dynamics. These non-biological factors form an important context for determining not just what we can do with epigenetic reprogramming, but what we should do.

Looking ahead, the field appears to be converging on a strategy of modest, incremental epigenetic remodeling rather than dramatic age reversal. The most promising approaches combine targeted epigenetic editing with other longevity interventions like senolytics or mTOR inhibitors. This multifaceted strategy may provide the benefits of youthfulness while staying well within safety thresholds. As research progresses, the focus is shifting from simply turning back the clock to optimizing the quality of aging, with epigenetic markers serving as guideposts rather than absolute targets.

The coming decade will likely see the first FDA-approved epigenetic age interventions, initially for specific age-related conditions rather than wholesale rejuvenation. These pioneering treatments will provide crucial safety data that could expand or constrain the boundaries of epigenetic resetting. For now, the scientific consensus emphasizes caution, with most researchers agreeing that we're better erring on the side of under-correction until we fully understand the long-term consequences of manipulating these fundamental biological programs.

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025