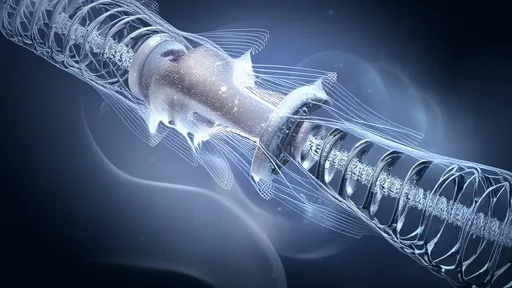

In a groundbreaking development that blurs the boundaries between species, scientists have achieved successful mitochondrial hybridization across evolutionary divides. This revolutionary technique, dubbed "xenomitochondrial transfer," allows for the transplantation of energy-producing organelles from one species to another while maintaining immunological compatibility. The implications are profound, ranging from novel therapeutic approaches to challenging our fundamental understanding of cellular symbiosis.

The mitochondria, often called the powerhouses of the cell, have their own distinct DNA separate from the nuclear genome. For decades, researchers have known that these ancient bacterial descendants play crucial roles beyond energy production - influencing everything from cellular signaling to programmed cell death. What makes this new breakthrough remarkable isn't just the cross-species transfer, but the team's ability to prevent immune rejection of these foreign organelles.

Immunological camouflage lies at the heart of this achievement. The research team developed a proprietary method to modify mitochondrial surface proteins without disrupting their electrochemical functions. By masking the organelles' foreign signatures, recipient cells perceive them as "self" rather than invading entities. Early experiments show these hybridized cells can sustain themselves for multiple generations while maintaining stable energy production levels.

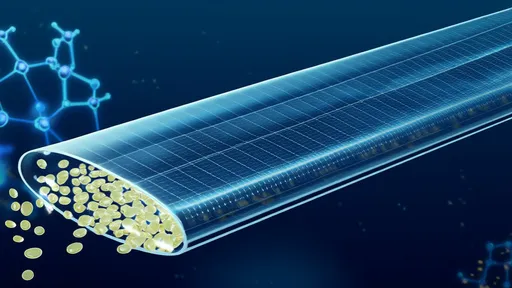

Dr. Elena Vasquez, lead researcher at the Singapore Institute of Cellular Engineering, describes the process as "teaching old organelles new tricks." Her team successfully transplanted dolphin mitochondria into human cultured cells with 87% viability after six months. "The dolphin mitochondria actually improved oxygen utilization efficiency in our human cell lines by nearly 15%," Vasquez notes. "This suggests we might harvest evolutionary advantages from marine mammals adapted to low-oxygen environments."

Ethical considerations have emerged alongside the technical triumphs. Some bioethicists question whether creating interspecies cellular hybrids crosses moral boundaries, while others highlight potential ecological concerns if modified mitochondria were to escape laboratory containment. The research team has implemented multiple safeguards, including "kill switches" that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis if certain environmental conditions change.

From a therapeutic standpoint, the applications appear staggering. Mitochondrial diseases affecting nearly 1 in 5,000 people could potentially be treated by replacing defective organelles with healthy versions from other species better suited to particular metabolic challenges. Imagine diabetes patients receiving mitochondria optimized for glucose metabolism from species with naturally high sugar tolerance, or neurodegenerative conditions being treated with organelles resistant to oxidative stress.

The military has taken notice as well. DARPA recently awarded a $12 million grant to explore whether soldiers could be equipped with mitochondria from extremophile species, potentially enhancing endurance in low-oxygen or high-radiation environments. While still speculative, the concept of "biologically augmented warfighters" has moved from science fiction to active research.

Commercialization efforts are already underway. Three biotech startups have licensed the core technology, with applications ranging from anti-aging cosmetics to high-performance athletics. One company, MitoSynergy, claims their preliminary tests show mouse mitochondria can boost racehorse performance by 8-12% without violating doping regulations since the enhancement comes from natural biological components.

As with any disruptive technology, regulatory frameworks struggle to keep pace. Current FDA guidelines don't specifically address cross-species organelle transfer, creating a gray zone for clinical applications. The World Health Organization has convened a special committee to establish international standards, but consensus remains years away given the complex scientific and ethical dimensions.

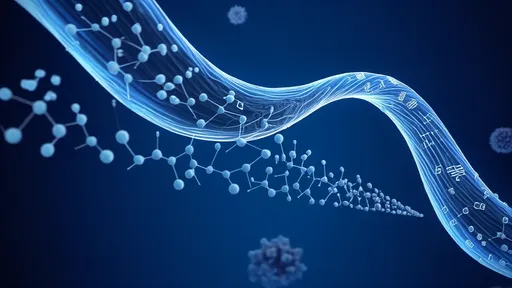

Looking ahead, the researchers aim to tackle even greater challenges. "Our next target is plant mitochondria," reveals Dr. Vasquez. "Imagine crops that could utilize animal mitochondria for more efficient energy conversion, potentially revolutionizing agricultural yields." The team has already begun preliminary work with chloroplast-mitochondria hybrid systems that could create entirely new pathways for photosynthesis.

This scientific frontier raises profound questions about the nature of biological identity. If a human cell contains mitochondria from multiple species, at what point does it cease to be purely human? Such philosophical quandaries will likely intensify as the technology progresses. For now, the scientific community remains focused on unlocking the tremendous potential of these hybrid energy factories while establishing robust safety protocols.

The coming decade may witness the first human clinical trials using xenomitochondrial transfer. If successful, we could be entering an era where our very cellular foundations become customizable across species barriers - a development that would redefine both medicine and our understanding of life's interconnectedness.

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025