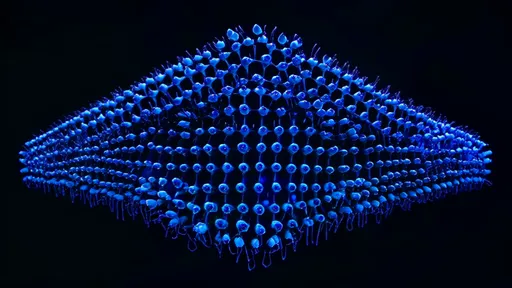

Nestled between the biology department and the engineering labs, a curious new structure has emerged on campus—dubbed the "Insect Radar Station." What looks like a futuristic lantern at first glance is actually a cutting-edge AI-driven system designed to monitor insect diversity through light trapping and real-time image recognition. This interdisciplinary project, spearheaded by entomologists and computer scientists, represents a quantum leap in ecological surveillance technology.

The hexagonal aluminum tower houses high-resolution cameras encircling a specialized UV light source that attracts nocturnal insects. Every 30 seconds, the system captures wing patterns, body segmentation, and antennae morphology with startling clarity. But the true magic happens in the custom-built neural network analyzing this constant stream of microscopic portraits. Unlike traditional monitoring that requires manual specimen collection, this system identifies species on the wing—literally.

Dr. Sylvia Chen, the lead entomologist, explains how the AI overcame initial skepticism: "We trained the model with over 800,000 verified insect images from museum collections. The breakthrough came when we incorporated temporal data—the system now recognizes that certain moths appear only after midnight, while mayflies swarm at dusk. It's learning the circadian rhythms of entire ecosystems." Early results have already identified three species of micro-moths previously unrecorded in the region, their faint wing markings overlooked by human observers for decades.

The engineering team faced unexpected challenges in adapting military-grade object recognition algorithms to the chaotic world of insects. "A fighter jet and a mosquito present very different tracking problems," laughs Professor Rajit Kapoor, holding up a circuit board speckled with moth scales. "We had to develop new filters to account for wingbeat frequency and flight trajectories. The current version can distinguish between nearly 3,000 taxa with 94% accuracy—better than most graduate students after a six-month field season."

Beyond academic curiosity, the project has urgent practical applications. The station's dashboard displays real-time graphs tracking population crashes of pollinator species alongside spikes in agricultural pests. Last autumn, it detected an unusual concentration of spotted lanternflies two weeks before campus arborists noticed the invasive species' damage—allowing targeted pesticide use that saved twelve heritage oaks. Such precision monitoring could revolutionize integrated pest management while reducing chemical spraying by up to 70%.

As the system expands to multiple campuses across climatic zones, researchers anticipate creating the first continent-scale insect migration map. The team recently added ultrasonic sensors to detect bat predation patterns, revealing invisible trophic relationships. "This isn't just about counting bugs," reflects Dr. Chen, watching the AI highlight a rare hawk moth on her tablet. "We're decoding an entire nocturnal universe that's been flying under humanity's radar—until now."

The project's open-source algorithms have sparked interest from vineyards monitoring pest outbreaks to public health agencies tracking mosquito vectors. Meanwhile, the mesmerizing light displays have become an unexpected campus attraction, with students gathering at dusk to watch the AI's identifications flash across an outdoor display. In an era of alarming insect declines, this marriage of entomology and artificial intelligence offers both rigorous data and something equally precious—a renewed sense of wonder for the small creatures that hold our ecosystems together.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025