In the shadow of nuclear disasters and industrial pollution, scientists are turning to an unlikely ally in the fight against toxic heavy metals: fungi. Recent breakthroughs in mycoremediation have unveiled the remarkable potential of fungal mycelium—particularly strains like Pleurotus ostreatus and Aspergillus niger—to bind and sequester cadmium from irradiated soils. This discovery could reshape environmental recovery strategies, especially in regions like Fukushima or Chernobyl, where radioactive contamination coexists with hazardous metals.

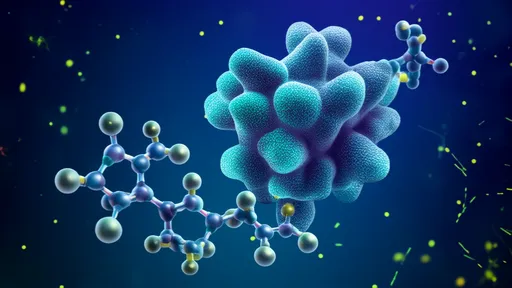

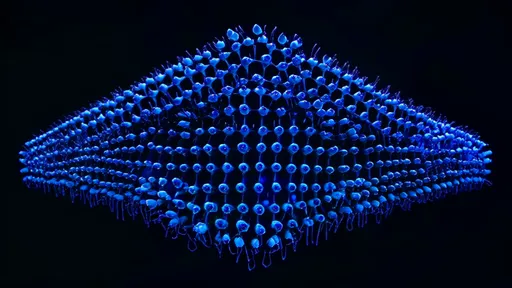

The magic lies in the mycelium’s intricate cellular architecture. Unlike conventional remediation techniques that often involve soil excavation or chemical treatments, fungal networks operate through passive biosorption. Their hyphal walls contain chitin, melanin, and functional groups (carboxyl, hydroxyl, and phosphate) that act like molecular Velcro for cadmium ions. Research from the University of Vienna demonstrates that some strains can adsorb up to 200 mg of cadmium per gram of biomass—a capacity rivaling industrial ion-exchange resins.

What makes this approach revolutionary is its self-replicating nature. Mycelium doesn’t just capture contaminants; it thrives in toxic environments, expanding its network to colonize larger soil volumes. A 2023 field trial in Belarus showed that inoculated plots reduced bioavailable cadmium by 78% within eight months, outperforming phytoremediation methods. The fungi achieve this through extracellular precipitation, transforming soluble Cd²⁺ into stable crystalline compounds like cadmium oxalate.

But the real breakthrough emerged when researchers noticed a synergistic effect in radiation-contaminated soils. Gamma irradiation appears to stimulate melanin production in certain fungi, enhancing their metal-binding capacity. This dual-action mechanism—where radiation damage inadvertently "primes" the fungi for better remediation—could explain why mycelium performs exceptionally well in nuclear accident zones. The melanin not only shields the fungus from radiation but also provides additional binding sites for heavy metals.

The practical implications are staggering. Imagine deploying fungal "ecocement" mats—pre-grown mycelium embedded in biodegradable substrates—across contaminated fields. As the fungus spreads, it simultaneously stabilizes the soil structure and immobilizes metals, preventing groundwater leaching. Unlike physical cleanup methods that generate secondary waste, mycoremediation leaves behind enriched organic matter. Pilot projects in Ukraine’s exclusion zone have already documented a 40% reduction in plant tissue cadmium concentrations after three growing seasons.

Challenges remain, of course. Soil pH, competing ions (like zinc), and microbial competition can affect performance. Yet genetic engineering offers solutions—teams at MIT recently spliced metallothionein genes from yeast into mycelium, creating strains with doubled cadmium uptake efficiency. As climate change intensifies soil degradation, these fungal technologies may become indispensable tools in our ecological toolkit, proving that sometimes, the best remedies grow quietly beneath our feet.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025