For decades, the miraculous navigational abilities of migratory birds have baffled scientists. How do these feathery travelers traverse thousands of miles with pinpoint accuracy, often returning to the same nesting grounds year after year? Recent breakthroughs in quantum biology suggest an astonishing answer may lie in the realm of quantum entanglement – a phenomenon where particles remain interconnected across vast distances.

The Quantum Compass Hypothesis proposes that certain bird species possess a biological "quantum entanglement shield" enabling them to perceive Earth's magnetic field through electron spin effects in their eyes. This radical theory challenges conventional understanding of both avian navigation and quantum physics' role in biological systems.

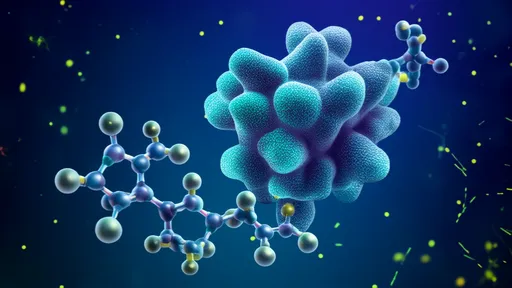

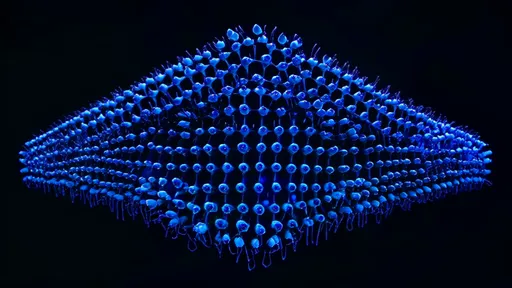

At the heart of this phenomenon lies a protein called cryptochrome, found in the retinas of migratory birds. When light hits cryptochrome molecules, it creates pairs of entangled electrons whose spin states become correlated. Earth's weak magnetic field, barely noticeable to most creatures, appears to influence these quantum states, providing birds with a visual magnetic map superimposed on their normal sight.

Laboratory experiments with European robins demonstrate that even extremely weak magnetic fields – just 15 nanotesla, about 1/100,000th of Earth's field – can disrupt their orientation when exposed to specific light wavelengths. This sensitivity suggests something far more precise than classical chemical reactions must be at work. The birds' apparent ability to maintain quantum coherence in these electron pairs at warm temperatures defies traditional expectations of quantum effects being limited to ultra-cold laboratory conditions.

Remarkably, this quantum biological compass appears to function as a kind of directional filter on the birds' visual perception. Researchers speculate that migratory species may literally see magnetic fields as patterns of light or color variations across their visual field. This would explain how Arctic terns can navigate from pole to pole or how homing pigeons find their way across unfamiliar terrain.

The implications extend far beyond ornithology. If biological systems can indeed harness quantum entanglement for sensory perception, it suggests nature evolved quantum technologies long before human scientists conceived of them. This discovery could revolutionize fields from neuroscience to quantum computing, potentially leading to new types of sensors that mimic biological quantum detection.

Challenges remain in fully understanding this phenomenon. The exact mechanism by which quantum spin states translate into neurological signals remains unclear. Some theorists propose that the entangled electron pairs create subtle chemical changes in the cryptochrome protein that nerve cells can detect. Others suggest more direct quantum interactions with cellular structures may be involved.

What's undeniable is that migratory birds appear to possess a biological quantum technology that our most advanced laboratories struggle to replicate. Their "quantum entanglement shield" against directional disorientation represents one of nature's most sophisticated adaptations – a living demonstration that the quantum and classical worlds intersect in ways we're only beginning to comprehend.

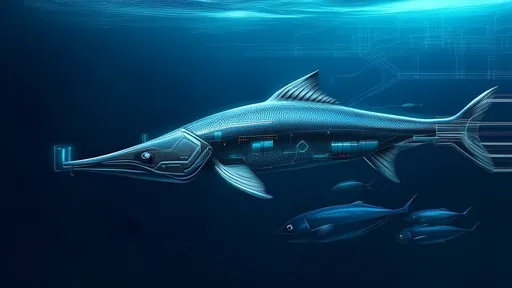

As research continues, scientists are exploring whether similar quantum effects might exist in other species, from sea turtles to butterflies. The discovery underscores how much we still have to learn about nature's hidden quantum dimensions and how biological systems exploit physics at its most fundamental level for survival and navigation.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025