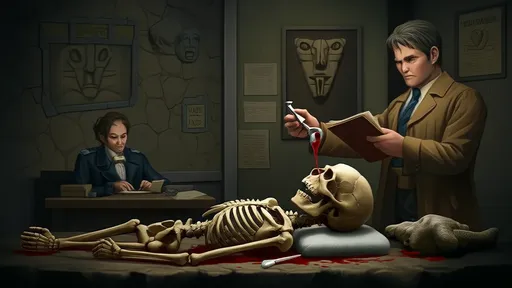

In a groundbreaking discovery that reads like a page from a forensic detective novel, scientists have unraveled a 3,000-year-old murder mystery using ancient proteins extracted from a victim’s teeth. The case, which had long been cold, was cracked open by a team of bioarchaeologists who turned to cutting-edge paleoproteomics—the study of ancient proteins—to identify the murder weapon. This marks the first time such techniques have been used to solve a prehistoric crime, offering a tantalizing glimpse into how modern science can breathe new life into cold cases buried deep in history.

The story begins with a skeleton unearthed in a Bronze Age burial site in what is now northern Germany. The remains, belonging to a man in his 30s, showed signs of violent trauma—a gaping hole in the skull suggested foul play. But the true breakthrough came not from bones, but from something far more unexpected: dental calculus, the hardened plaque on the victim’s teeth. Trapped within this mineralized time capsule were traces of proteins that shouldn’t have been there—proteins matching those found in the venom of the European adder, a venomous snake native to the region.

What emerged was a chilling scenario: The man had been bitten by an adder shortly before his death. But here’s where the plot thickens—the snakebite alone wouldn’t have been fatal. The skull fracture told another story. Researchers now believe the victim was first attacked with a blunt object, then finished off with a staged snakebite, possibly to make the murder look like an accident. "This was premeditated," says Dr. Helena Vestergaard, lead researcher on the study. "Someone knew adder bites were common in the area and tried to use nature as a cover for murder."

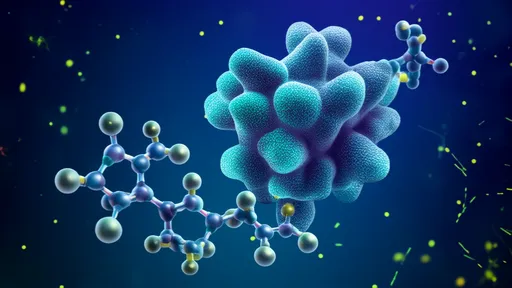

The detective work didn’t stop there. By analyzing the protein degradation patterns, the team could even estimate the time between the snakebite and death—less than 24 hours. This level of temporal resolution is unprecedented in ancient crime reconstruction. Moreover, isotopic analysis of the teeth revealed the victim wasn’t local; he’d migrated from southern Europe, making him an outsider in the community. Was this a crime of passion? A ritual killing? Or the Bronze Age equivalent of a gangland hit? The proteins can’t tell us that, but they’ve given investigators their first solid lead in three millennia.

This case sets a remarkable precedent for archaeological forensics. Traditionally, researchers relied on bone fractures and burial contexts to interpret ancient violence. Now, paleoproteomics adds another layer to our understanding—one that operates at the molecular level. The technique is particularly valuable because proteins survive much longer than DNA in archaeological contexts, especially in dental calculus which acts as a natural preservative. "Teeth are time machines," remarks Dr. Vestergaard. "They record biological events like tree rings record droughts."

The implications extend beyond this single case. Across Europe, numerous Bronze Age skeletons show signs of trauma whose causes remain mysterious. Could snake venom proteins lurk in their dental calculus too? The team is now re-examining other suspicious ancient deaths with their new forensic toolkit. There’s even talk of creating an "ancient cold case unit" specializing in paleoproteomic investigations—a sort of CSI: Bronze Age.

Yet challenges remain. Unlike modern forensic labs where contamination controls are strict, archaeological samples come with 3,000 years of environmental exposure. Distinguishing between ancient proteins and modern contaminants requires painstaking protocols. The team had to account for everything from 20th-century pesticide exposure to the glue used in museum conservation. "It’s like trying to hear a whisper in a hurricane," admits protein analyst Dr. Raj Patel. "But when you finally isolate that authentic signal, it’s electrifying."

As for the Bronze Age murderer? Their identity may never be known. But thanks to science’s newest detective tool, their crime—hidden for thirty centuries—has finally come to light. And with each ancient case solved, we gain not just knowledge about individual acts of violence, but about the broader social tensions of prehistoric societies. After all, as the researchers note, murder is one of humanity’s oldest traditions—and now, so too is the science of solving it.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025