In the crushing darkness of the ocean's deepest trenches, where pressures exceed 2000 atmospheres and temperatures hover near freezing, scientists have discovered microbial "enzyme alchemists" capable of performing one of biology's most challenging feats: nitrogen fixation under extreme conditions. This groundbreaking finding, published in Nature Microbiology, rewrites our understanding of life's biochemical limits and opens new possibilities for industrial applications.

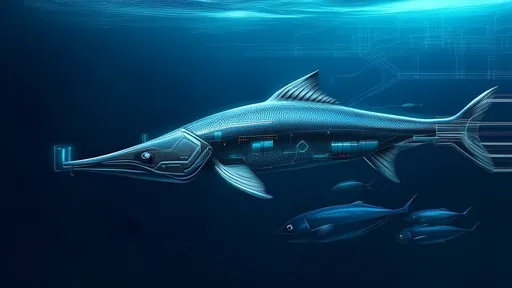

The international research team, led by marine microbiologists from the University of Tokyo and the Max Planck Institute, deployed specialized deep-sea sampling equipment to collect sediment cores from the Mariana Trench's hadal zone, approximately 10,900 meters below sea level. What they found in these extreme environments challenges conventional wisdom about the physical limits of enzymatic activity.

"These trench-dwelling microbes have essentially redefined what we thought possible for biological nitrogen fixation," explains Dr. Hiroshi Matsumura, senior author of the study. "At pressures that would instantly crush most laboratory equipment, their nitrogenase enzymes continue functioning with remarkable efficiency." The discovery suggests that life has evolved biochemical adaptations far beyond what scientists previously considered the survivable threshold.

Nitrogen fixation, the process of converting atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) into biologically useful ammonia (NH₃), typically occurs under relatively mild conditions in surface-dwelling bacteria and archaea. The newly discovered hadal microbes accomplish this same feat at pressures 2000 times greater than at sea level, where the weight of overlying water creates an environment more extreme than the surface of Venus.

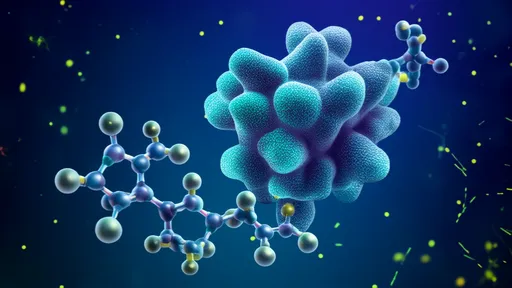

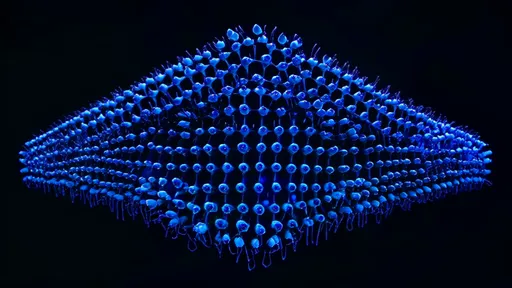

The researchers employed cutting-edge metagenomic sequencing to identify the unique genetic adaptations in these microbial communities. Their analysis revealed several surprising modifications to the standard nitrogenase enzyme complex, including structural reinforcements at key catalytic sites and specialized pressure-resistant protein folding patterns. These adaptations appear to have evolved independently of known nitrogen-fixing pathways, suggesting a completely novel biochemical strategy for operating under extreme conditions.

Perhaps most astonishing is how these "high-pressure alchemists" maintain metabolic activity in what scientists previously considered a near-lifeless zone. The team's measurements show nitrogen fixation rates at depth comparable to those observed in shallow-water microbial mats, despite the enormous energetic costs imposed by the extreme environment. This finding forces us to reconsider the biochemical potential of life in Earth's most inaccessible habitats - and potentially on other worlds with similarly extreme conditions.

The discovery has immediate implications for several fields. In biotechnology, these pressure-adapted enzymes could revolutionize industrial ammonia production, which currently requires the energy-intensive Haber-Bosch process operating at high temperatures and pressures. By harnessing these naturally evolved high-pressure catalysts, engineers might develop more efficient methods for fertilizer production and other nitrogen-dependent processes.

Astrobiologists are particularly excited by the implications for the search for extraterrestrial life. Ocean worlds like Europa and Enceladus likely harbor similar high-pressure environments beneath their icy shells. "If life can fix nitrogen under these conditions on Earth," notes NASA astrobiologist Dr. Lisa Kaltenegger, "it dramatically increases the possible habitable zones we should consider in our search for life elsewhere in the solar system."

The research team faced extraordinary technical challenges in verifying their findings. Maintaining samples at in situ pressures during retrieval and analysis required custom-built pressurized chambers and specialized equipment originally developed for deep-sea oil exploration. "We essentially had to reinvent standard laboratory protocols from the ground up," says co-author Dr. Elena Petrova. "Every step - from DNA extraction to enzyme assays - needed to be reengineered to prevent pressure shock to the samples."

Further investigation revealed that these microbial communities form intricate symbiotic relationships with other trench organisms, creating complete high-pressure ecosystems powered by nitrogen fixation. The fixed nitrogen appears to support diverse food webs in what was once considered a biological desert. This discovery helps explain how complex life persists in the deep ocean's most inhospitable regions.

Looking ahead, the research team plans to culture these remarkable microbes under controlled laboratory conditions to study their biochemical pathways in greater detail. They also aim to explore other deep-sea trenches worldwide to determine how widespread this high-pressure nitrogen fixation capability might be. Early indications suggest similar microbial communities may exist in the Kermadec, Japan, and Puerto Rico trenches, potentially representing a global phenomenon.

Beyond the scientific implications, this discovery highlights how much we still have to learn about life on our own planet. As Matsumura reflects: "Every time we think we've found the limits of life, the deep ocean shows us how little we truly understand. These microbial alchemists aren't just surviving under impossible conditions - they're thriving and performing biochemistry that challenges our fundamental assumptions."

The findings also raise provocative questions about the origins of these adaptations. Did these microbes evolve their high-pressure capabilities gradually as tectonic shifts carried them deeper over millennia? Or were their ancestors somehow pre-adapted to extreme conditions? The research team's phylogenetic analyses suggest these lineages diverged from known nitrogen-fixers at least 500 million years ago, potentially coinciding with major geological changes in ocean basin formation.

Industrial partners are already exploring applications for these pressure-resistant enzymes. One promising avenue involves developing biocatalysts for deep-sea bioremediation, where standard microbial treatments fail under extreme pressures. Other teams are investigating whether these enzymes' unique properties could improve nitrogen delivery in agricultural systems or enable novel approaches to carbon capture.

As with many deep-sea discoveries, this finding came with a sobering realization: human activities may be affecting these ecosystems before we fully understand them. The researchers detected trace amounts of microplastics and persistent organic pollutants in their trench samples, demonstrating that even these remote environments aren't immune to anthropogenic impacts. Protecting these newly discovered biochemical wonders may become an unexpected conservation priority.

The study represents more than just a record-breaking extremophile discovery. It fundamentally expands our conception of where and how critical biogeochemical processes can occur. As we continue exploring Earth's final frontiers, these deep-sea enzyme alchemists remind us that nature's ingenuity often surpasses our imagination - and that the most remarkable discoveries may still lie waiting in the darkness below.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025