Deep in the forest, an intricate and silent exchange unfolds beneath the soil. Mature oak trees, some scarred by storms or disease, extend a lifeline to struggling seedlings through an underground network of fungi. This phenomenon, whimsically dubbed the "Philanthropic Red Cross of Plants," reveals a hidden economy of nutrient sharing that challenges traditional notions of competition in nature.

The discovery emerged from decades of research into mycorrhizal networks—the symbiotic relationships between plant roots and fungal hyphae. Scientists have long known these fungal threads act as nutrient highways, but new evidence shows damaged adult oaks preferentially diverting resources to younger trees. "It's as if the forest maintains its own triage system," observes Dr. Elena Vogt, a mycologist at the Swiss Federal Research Institute. Her team's isotopic tracing experiments proved injured trees increase carbohydrate transfers through fungal connections by up to 300% compared to healthy specimens.

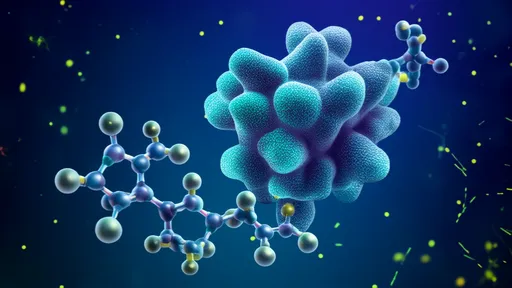

What triggers this arboreal altruism? The mechanism appears exquisitely sensitive. When an oak suffers physical damage or insect attacks, its root chemistry changes within hours. Specific stress hormones like methyl jasmonate alert the fungal network, which responds by widening its nutrient transport channels toward nearby seedlings. Remarkably, the assistance isn't random—genetic analysis shows related saplings receive more support than unrelated neighbors, suggesting plants can distinguish kin through biochemical signatures.

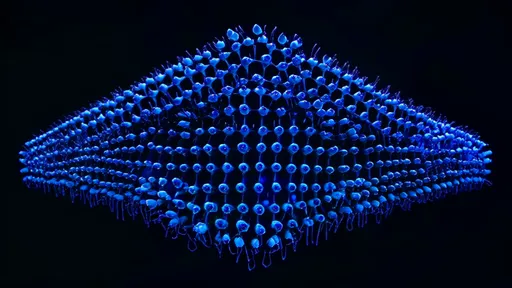

This underground welfare system carries profound ecological implications. In old-growth forests where light penetration is limited, up to 80% of seedling carbon may derive from these fungal subsidies. The findings overturn textbook dogmas of cutthroat competition, revealing instead a sophisticated interplay of cooperation and kinship selection. "We're witnessing the evolution of mutual aid at geological timescales," notes Dr. Vogt. Some mycorrhizal networks have persisted for millennia, their hyphal threads physically connecting generations of trees.

The "wood wide web" exhibits startling complexity. Certain fungal species specialize in redistributing nitrogen during droughts, while others shuttle phosphorus to seedlings in deep shade. This division of labor mirrors human social systems, with distinct roles for resource bankers, transporters, and emergency responders. During bark beetle outbreaks, healthy oaks even appear to "donate" defensive compounds to infected neighbors through fungal intermediaries—a phenomenon researchers compare to botanical vaccination campaigns.

Yet this benevolent network faces modern threats. Atmospheric nitrogen pollution from agriculture disrupts the delicate chemical signaling between trees and fungi. In Germany's Black Forest, areas with elevated nitrogen show 60% fewer mycorrhizal connections and dramatically reduced seedling survival. "We're not just losing trees," warns Dr. Vogt, "we're erasing the very infrastructure that allows forests to regenerate." Climate change compounds the damage, as drought conditions cause fungi to retreat deeper underground, severing the lifelines to vulnerable saplings.

Conservation efforts now prioritize protecting these invisible networks. Some forward-thinking foresters inoculate logged areas with native fungal spores, while others advocate for "mother tree" policies that preserve central hub trees during timber harvests. The most radical proposals suggest granting legal protection to critical mycorrhizal networks—a recognition that forests function more as superorganisms than collections of individual plants.

As research continues, each discovery unveils deeper layers of arboreal interdependence. From carbon trading to chemical warnings, the forest floor hums with conversations we're only beginning to decipher. The wounded oaks stand not as symbols of decay, but as keystones in an ancient system of communal resilience—their gnarled roots writing checks that saplings cash in sunlight.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025