The ocean's most enigmatic communicators may not be dolphins or whales, but creatures with eight arms and color-changing skin. New research reveals that octopuses employ a sophisticated "skin semantic web" – a dynamic system of pigment cell combinations that transmits precise hunting collaboration signals to their peers. This groundbreaking discovery challenges our fundamental understanding of cephalopod communication and redefines the complexity of invertebrate intelligence.

For decades, scientists marveled at octopuses' rapid chromatic displays without grasping their full significance. What appeared as simple camouflage or emotional expression actually constitutes a rich visual language. Marine biologists at the Lembeh Strait Research Station have documented over 1,700 distinct pigment cell configurations in the day octopus (Octopus cyanea), with 17 recurring patterns specifically linked to cooperative foraging behaviors. When hunting in pairs, these cephalopods create real-time skin mosaics that coordinate attack strategies with remarkable precision.

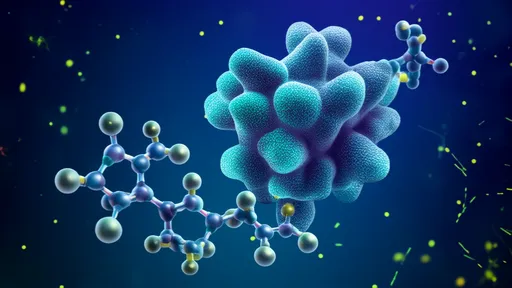

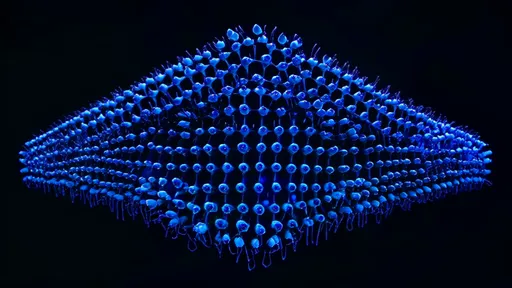

The mechanics involve three interacting chromatophore layers creating combinatorial signals. Upper xanthophores project yellow-orange hues while deeper iridophores reflect structural colors, all controlled by neural impulses faster than human visual processing. During coordinated hunts, partners mirror specific pattern sequences – a striped "commitment signal" followed by pulsating dots indicating attack vectors. This occurs despite octopuses being colorblind, suggesting their skin interprets light wavelengths directly.

Field observations captured an extraordinary example: two octopuses encircling a crab colony executed perfectly synchronized color shifts. One displayed radial stripes while its partner showed mottled brown, creating a "moving net" illusion that herded prey. Subsequent analysis revealed these patterns never occur during solitary hunting. "It's akin to football players calling audibles through jersey flashes," noted Dr. Hana Elazar, lead researcher. "The skin becomes both signal and receiver in their communication matrix."

This phenomenon appears most developed in reef-dwelling species facing complex predation challenges. The Caribbean reef octopus (Octopus briareus) demonstrates even more advanced syntax – alternating skin textures with color patterns to indicate prey size and escape routes. Juveniles learn these signals through observational conditioning, proving the system's cultural transmission aspect. Remarkably, different populations exhibit "dialectal variations" in their chromatic coding, much like regional human language differences.

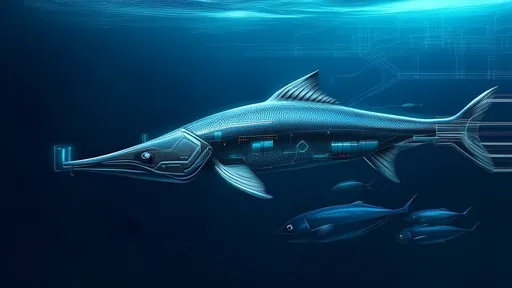

The implications extend beyond marine biology. Robotics engineers at Singapore Polytechnic are developing soft robots using octopus-inspired chromatic signaling for swarm coordination without centralized control. Meanwhile, neuroscientists reevaluate consciousness models, as this distributed intelligence operates without a cerebral cortex. The octopus skin web suggests evolution arrived at advanced communication through entirely different pathways than vertebrate social species.

As ocean acidification threatens cephalopod populations, researchers race to document this vanishing communication art. Over 60% of observed signal combinations remain undeciphered, hinting at deeper layers of complexity. These findings ultimately blur the line between skin and brain, redefining how we perceive intelligence in Earth's most alien minds.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025