In a groundbreaking fusion of marine biology and robotics, researchers have developed a new generation of bio-inspired robotic fish capable of executing rapid turns with unprecedented agility. The breakthrough comes from decoding the hydrodynamic secrets of tuna – some of the ocean's most efficient swimmers. This innovation could revolutionize underwater exploration, search-and-rescue operations, and even naval defense strategies.

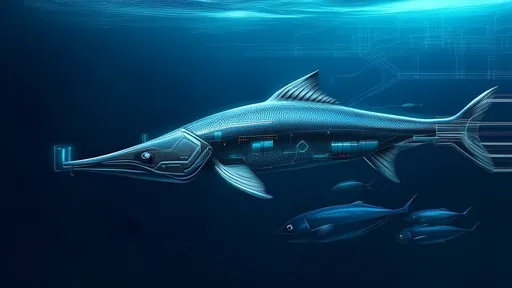

The tuna's remarkable ability to execute high-speed directional changes has long fascinated scientists. Unlike rigid-bodied robotic systems, these fish employ a sophisticated combination of body flexion, fin articulation, and fluid dynamics that essentially turns their entire body into a "fluid computer." Researchers at the Marine Robotics Laboratory have spent eight years reverse-engineering these natural mechanisms, leading to the creation of their flagship robotic tuna prototype, ARTEMIS-7.

What sets this research apart is the team's focus on the tuna's non-intuitive turning strategy. "The fish doesn't just bend its body and hope for the best," explains Dr. Helena Zhang, lead hydrodynamicist on the project. "There's a precise sequence of muscle activations that creates a traveling wave along its body, while the caudal fin executes what we've termed a 'hydrodynamic pivot' – essentially using water resistance as a computational medium to optimize the turn."

The robotic implementation required developing new soft actuators that mimic the tuna's white muscle fibers, capable of rapid contractions. These are arranged in a biomimetic pattern along the robot's flexible silicone body. Pressure sensors covering the surface provide real-time fluid dynamic feedback, creating what the team calls a "mechanical neural network" that processes hydrodynamic information analogously to how the fish's lateral line system operates.

Field tests in open water have demonstrated startling performance. The 1.8-meter robotic tuna can execute a 90-degree turn within 0.7 body lengths – matching its biological counterpart. This represents a 40% improvement over previous robotic fish designs and outperforms most propeller-driven underwater drones in maneuverability tests. The achievement is particularly remarkable because it was accomplished without traditional computational fluid dynamics modeling, instead relying on the emergent properties of the bio-inspired design.

Military observers have taken keen interest in the technology's potential applications. The robotic fish's silent operation and natural movement pattern make it nearly indistinguishable from real marine life, offering obvious advantages for covert surveillance. However, the research team emphasizes the civilian applications, particularly in delicate underwater environments where traditional ROVs might damage coral reefs or disturb archaeological sites.

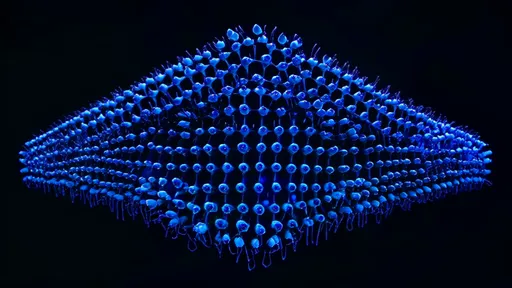

Looking ahead, the team is working to scale down the technology for swarm applications. "Imagine hundreds of these robotic fish working in concert to map ocean currents or monitor pollution," says Dr. Zhang. "The fluid computation concept means they could share hydrodynamic information collectively, creating a true underwater internet of things." Early tests with smaller prototypes show promise, with five robotic fish successfully maintaining formation while navigating complex currents.

Commercialization remains several years away, as the team continues to refine the technology. Current challenges include improving battery life – the high-energy maneuvers drain power quickly – and developing more robust sensor systems for long-term operation in harsh marine environments. Nevertheless, this research represents a significant leap forward in soft robotics and biologically inspired engineering, proving once again that nature's solutions often outpace human imagination.

The implications extend beyond marine robotics. The fluid computation principles discovered through this research may find applications in aerospace design, where managing fluid dynamics is equally crucial. Some automotive engineers are already exploring how similar concepts could improve the aerodynamics of high-performance vehicles. As Dr. Zhang observes, "We're just beginning to understand how biological systems compute with their environment – this is potentially a whole new paradigm for engineering."

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025